Fort Chaplin Park

Washington, DC | 2016

Cultural Landscape Inventory

Project Team: Randall Mason, Molly Lester

History

Fort Chaplin was one of the 68 forts built as a defensive ring around Washington during the Civil War. It was constructed late in the war, as one of three forts erected in 1864 to bolster the ring of defenses soon after Confederate General Jubal Early’s attack on Fort Stevens. Built on the land of Shelby Scaggs, the fort was named for Colonel Daniel Chaplin, 1st Maine Heavy Artillery, who was killed in Virginia shortly before construction on the fort commenced.

Fort Chaplin was built to strengthen Fort Mahan, which was located north of Fort Chaplin and responsible for guarding the Benning Road Bridge to the capital. The fort had an irregular, 11-sided perimeter that measured 225 yards; the sally port was located at the southwest corner of the earthworks. The entire hill around the fort was clear-cut to ensure views north and east of the District of Columbia. Although the fort was never fully armed and was never garrisoned, it did have twelve gun emplacements (one of which was added after its initial construction).

At the conclusion of the war in 1865, the fort was among the designated “second-class” forts east of the Anacostia River. Forts in this category were considered to be “generally in good order, and would last many years without much expenditure of labor or money. They [occupied] positions which must be held when the city is threatened by land attack. They [were] not so important, however, as the forts named in the first class.” As a result, Fort Chaplin was decommissioned by December 1865; Selby Scaggs, who owned the land prior to the war, retook possession of the fort and its surrounding land.

According to historic maps and descriptions of the area around Fort Chaplin, the earthworks remained in place and clear-cut on the site into the late nineteenth century, even as the surrounding landscape reverted to agricultural use. The former Scaggs house remained intact, as did a few other structures further west on the site, along Eastern Branch Road; these buildings likely survived until the 1930s. Circulation through the site was irregular through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as fragments of the old military road remained intact but other trails and roads deteriorated.

In 1902, the publication of the McMillan Plan spurred efforts to preserve Fort Chaplin as part of a circle of green spaces around the city. This ring of parks would be established on the former sites of the Civil War Defenses of Washington, as part of the City Beautiful movement’s re-envisioning of the District of Columbia. Fort Chaplin was, by this time, surrounded by limited development, and the site itself featured a few of houses around its periphery. Because of this relatively sparse development, as well as the incomparable vistas from Fort Chaplin and its nearby defenses, the McMillan Plan considered the parks east of the Anacostia River to be particularly important for the future greenway, with “the most beautiful of the broad views to be had in the District.”

The District’s efforts to acquire the land stalled until the late 1920s, when the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) was authorized to purchase land related to the Civil War Defenses of Washington. A year later, on April 30, 1926, Congress replaced NCPC with the larger and more empowered National Capital Park and Planning Commission (NCPPC), and in 1927, and the NCPPC began acquiring parcels of land to convert fort sites into parks. Fort Chaplin was one of the later acquisitions, with the first purchase completed in 1935. By 1939, Fort Chaplin Park was at its largest size since the Civil War. Beginning in the 1940s, however, the park’s boundaries were trimmed, due to both the formalization of the street pattern around the fort (including the introduction of East Capitol Street along the park’s northern edge), as well as various land deals that transferred acreage to other District of Columbia agencies.

Analysis + Evaluation

Today, Fort Chaplin is situated in the midst of a largely residential area of southeast Washington, DC, with the major thoroughfare of East Capitol Street running east-west along its northern border. Its Civil War earthworks are largely deteriorated or overgrown, although some remnants are visible. The landscape retains portions of the vegetation pattern from its twentieth-century conversion to a park, although the density of the vegetation at the hilltop affects various features of the landscape.

Fort Chaplin exhibits the following landscape characteristics: topography, spatial organization, land use, buildings and structures, circulation, vegetation, views and vistas, small-scale features, and archaeology.

Topography: The site for Fort Chaplin was selected for its topography. Its position at approximately 180 feet above sea level provided an elevated vantage of the surrounding landscape, including several strategic sites that Fort Chaplin was designed to protect. The topography remains the same as it was throughout the historic period, and retains a high degree of integrity.

Spatial Organization: The spatial organization of the Fort Chaplin cultural landscape dates to the later period of significance, when the site was converted to a park. There have been minor additions to the landscape in the form of wayfinding and interpretive signs since the later period of significance, but the site retains its historic spatial organization and has a high degree of integrity.

Land Use: The military land-use aspect of the Fort Chaplin cultural landscape ended when the United States government sold the property in 1865. However, the land use at Fort Chaplin has not changed since the 20th century period of significance (1902-1939). The site remains a public park, and is used for recreation, education, and interpretation. The park continues to serve a public function and is open for general recreational use. Land use at Fort Chaplin retains integrity.

Buildings and Structures: The site has some integrity of buildings and structures from its nineteenth-century period of significance (1861-1865). Portions of Fort Chaplin’s earthworks remain intact; this includes remnants of the sally port, bombproof, magazine, and fragments of parapet walls. However, these features are generally collapsed and deteriorated. No other buildings or structures survive from the periods of significance, and no other structures are extant within the current park boundaries. Fort Chaplin retains partial integrity of buildings and structures due to the surviving earthwork fragments.

Circulation: A small portion of Fort Chaplin’s Civil War-era military road survives as the primary circulation feature from the nineteenth-century period of significance. The extant social trails may date in part or in full to the twentieth-century period of significance, but this cannot be confirmed. All extant circulation features are difficult to access and generally difficult to discern in the current landscape due to the relatively heavy vegetation; this has an adverse effect on the integrity of the site’s circulation. The site therefore retains some integrity of circulation.

Vegetation: There was limited vegetation at Fort Chaplin during the Civil War, in keeping with the site’s strategic design and use. The current vegetation pattern is not, therefore, consistent with the nineteenth century period of significance. The current vegetation pattern is generally consistent with the twentieth-century period of significance. However, the current density of the site’s vegetation, including mature trees and brush that have overtaken large areas of the park and the earthworks, detract from the integrity of the site. Fort Chaplin does not retain integrity of vegetation.

Views and Vistas: The views and vistas from Fort Chaplin during the Civil War extended to the countryside surrounding the fort—in particular, towards the north and east. These vistas remained intact for several decades after the war, but the redevelopment of the site and the surrounding area in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries affected the views from the landscape at Fort Chaplin. In addition, during the later period of significance, vegetation growth within the site also affected the significant nineteenth-century views. Fort Chaplin’s views and vistas do not retain integrity.

Small-Scale Features: Fort Chaplin’s small-scale features do not retain integrity. The site has no surviving features from its nineteenth century period of significance. The site’s extant features, including signage (regulatory, wayfinding, and interpretive) and a trash can on the southern edge of the park, postdate the twentieth-century period of significance and are non-contributing. The small-scale features of Fort Chaplin’s cultural landscape therefore do not retain integrity.

Archaeology: Fort Chaplin retains archaeological integrity. Although the site has seen limited archaeological investigation to date, it is highly likely that future archaeological study of the area around Fort Chaplin will locate additional resources from the Civil War-era period of significance. Additionally, resources dating to the second period of significance and the site’s use for recreation may be discovered, and would help shed light on twentieth-century alterations to the area.

Comparison of the site of Fort Chaplin, as depicted on the 1861 Boschke map (left) and the 1861 Lines of Defense map (right), developed by Major General John G. Barnard. Barnard’s map of the fortifications around Washington used Boschke’s survey as a base map, superimposing the location of the hastily-built forts on the existing map. (Boschke 1861; Lines of Defense map, via HistoricMapWorks.com)

Engineer drawings of Fort Chaplin, including plan (center) and sections of the earthworks. (National Archives, as printed in Cooling and Owen 2010)

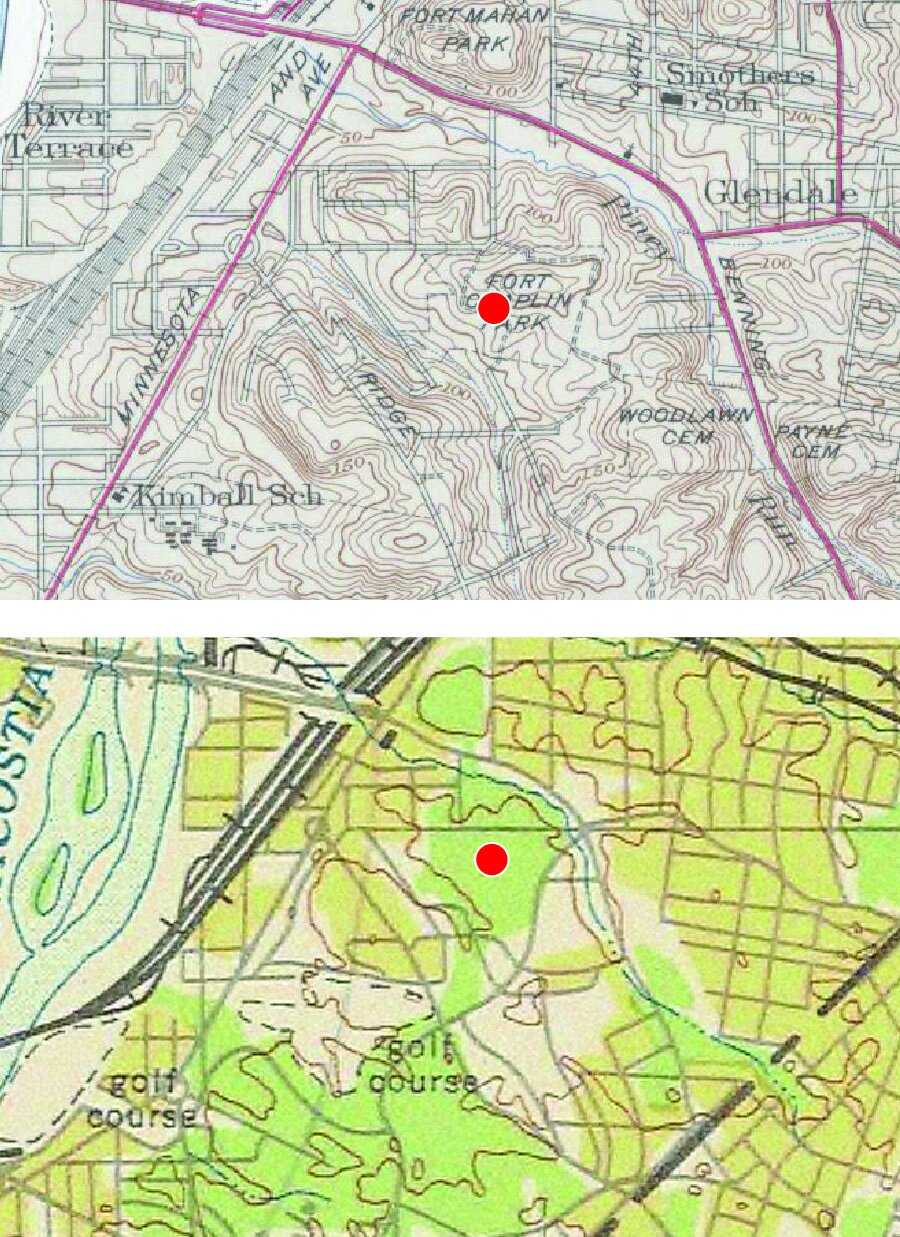

Fort Chaplin’s historic fabric, as seen in 1884 (top) and 1888 (bottom). The approximate location of the earthworks is indicated in the 1884 map by a red dot. (Lydecker and Greene 1884; United States Geological Survey 1888)

A map of Fort Chaplin and its setting in 1895, denoting the surviving fragments of the earthworks (right), former military road (center), and vegetation. (United States Coast and Geodetic Survey 1895)

The buildings, structures, and setting of Fort Chaplin, as seen in 1907 (top) and 1927 (bottom). The approximate location of the surviving earthworks is indicated on each map by a red dot. (Baist 1907, via HistoricMapWorks.com; Baist 1927, via HistoricMapWorks.com)

The evolution of Fort Chaplin’s footprint and boundaries in the mid-twentieth century, as seen in maps from 1945 (top) and 1949 (bottom). The approximate location of the extant earthworks is indicated in each map by a red dot. Among the changes that affected Fort Chaplin during these years, East Capitol Street was extended eastward, and Texas Avenue SE was created along the park’s eastern boundary. (United States Geological Survey 1945; United States Air Force 1949)

Footprint of the earthworks at Fort Chaplin, as seen in an 1888 map (top) and recent aerial photography (bottom); portions of the parapets can be seen at the center of the photograph. (United States Geological Survey 1888; Digital Globe-Sanborn/Google Earth 2003)

Extant conditions of the earthworks, including parapet remnants (top) and the area between the bomb proof and the magazine (bottom). (M. Lester 2016)

Historic circulation patterns at Fort Chaplin (top), as of 1888 (with fragments of Civil War-era features), and current circulation patterns (bottom), with fragments of social trails and the historic military road. (United States Geological Survey 1888; Digital Globe/Google Earth 2012)

Extant circulation features in Fort Chaplin Park include a portion of the historic military road (top) and the Fort Circle Parks hiker-biker trail (bottom), which extends through Fort Chaplin Park and crosses over into adjacent lands. (M. Lester 2016)

Existing conditions of social trails on the site. At their entrances (left), social trails are generally legible; on the interior of the site, however (right), they are difficult to distinguish and follow. (M. Lester 2016)

Historic vegetation conditions on the site during the nineteenth-century period of significance, when Fort Chaplin was clear-cut (top), as compared with current vegetation patterns on the site, with mature trees throughout. The approximate location of extant earthworks is indicated in each image by a red dot. (Lydecker and Greene 1884; USDA Farm Service Agency/Google Earth 2011)

Existing vegetation conditions around the perimeter of the site. The northern boundary (top), located along East Capitol Street, features a narrow grassy strip between the hillside and the sidewalk, while the southern boundary (bottom) on C Street SE has a narrower grassy strip between park and the street. (M. Lester 2016)

General vegetation conditions, including mature trees and ground cover throughout the site (top) and extensive brush and tree stands covering the earthworks (bottom). (M. Lester 2016)

Current views from Fort Chaplin Park, obstructed by vegetation—particularly on the surviving earthworks. (M. Lester 2016)